FZMw Jg. 6 (2003) S. 53-64

by Tim Ovens

HTML-Schnellansicht

PDF-Format * * * ABSTRACT

1

In my lecture I would like to follow the way - John Cage's way through the world of sounds, the way to the prepared piano and beyond. I want to show the determination with which Cage ever more and more extended his sound collection, his musical cosmos. Of course, the line of this development is not as even as I describe it here. There are jumps and overlaps, which I do not mention in my lecture, in order to clarify things a little. So please excuse my simplifications in the description of John Cage as a sound collector.

2

'My favourite music is the music I haven't heard yet.'[2] During his whole life Cage was on the search for new sounds. Doing so, he did show an impressive inventiveness in his way of composing. An inventiveness he possibly inherited from his father John Milton Cage.

'My father was an inventor. He was able to find solutions for problems of various kinds, in the fields of electrical engineering, medicine, submarine travel, seeing through fog, and travel in space without the use of fuel. He told me if someone says "cant" that shows you what to do.'[3]

Maybe this is I dare to say this a typical American pragmatism, which John Cage will show later again and again.

3

To understand Cage's lifelong interest in various sounds, let us first take a look at a little story in Cages early life. Cage - at the age of eighteen years - had first begun to study architecture in Paris. It soon became clear to him, that he did not want to devote his life to architecture, as his teacher demanded.

SEITE: 53

'I left Paris and began both painting and writing music, first in Mallorca. The music I wrote was composed in some mathematical way I no longer recall. It didnt seem like music to me so that when I left Mallorca I left it behind to lighten the weight of my baggage. In Sevilla on a street corner I noticed the multiplicity of simultaneous visual and audible events all going together in ones experience and producing enjoyment. It was the beginning for me of theatre and circus.'[4]

4

So we can see that already at this time the variety of most diverse sounds attracts him. First of all, however, Cage returns to California and here he takes traditional composition lessons. His first teacher is Richard Buhlig; afterwards he goes to Henry Cowell. Cowell again recommends to him to take lessons with Arnold Schoenberg, who at that time already lived in Los Angeles.

'When I asked Schoenberg to teach me, he said, "You probably cant effort my price." I said, "Dont mention it; I dont have any money." He said, "Will you devote your life to music?" This time I said "Yes." He said he would teach me free of charge. I gave up painting and concentrated on music.'[5]

5

The first pieces of John Cage for example the Two Pieces for Piano from 1935 - clearly show the influence of Schoenberg, with their beginnings having traces of serial composition techniques. The two composers' different views on art, however, soon become unbridgeable:

'After two years it became clear to both of us that I had no feeling for harmony. For Schoenberg, harmony was not just coloristic: it was structural. It was the means one used to distinguish one part of a composition from another. Therefore he said Id never be able to write music. "Why not?" "Youll come to a wall and wont be able to get through." "Then Ill spend my life knocking my head against that wall."'[6]

Years later Schoenberg spoke about John Cage: 'Naturally hes no composer, but rather an inventor - an ingenious inventor.'[7]

SEITE: 54

6

Thus Cage's composition studies came to their end. In the following years Cage gets by with odd jobs beside his composition activities. In 1936 he becomes assistant to the film producer Oscar Fischinger. Fischinger is at that time one of the most well-known and most successful experimental film makers. Remarkable above all is the conversion of music into cinematic motion by graphic structures and geometrical patterns.

'He happened to say one day, "Everything in the world has its own spirit which can be released by setting it into vibration." I began hitting, rubbing everything, listening, and then writing percussion music, and playing it with friends.'[8]

7

The percussion music John Cage wrote at that time was mainly music for dance; because since 1937 Cage was employed by the Cornish School as a composer and accompanist of a dance company. Here Cage invented the prepared piano with his piece Bacchanale.

'Before I left the Cornish School I made the prepared piano. I needed percussion instruments for music for a dance that had an African character by Syvilla Fort. But the theatre in which she was to dance had no wings and there was no pit. There was only a small grand piano built in the front and left of the audience.

At the time I either wrote twelve-tone music for piano or I wrote percussion music. There was no room for the instruments. I couldnt find an African twelve-tone row. I finally realised I had to change the piano. I did so by placing objects between the strings. The piano was transformed into a percussion orchestra having the loudness, say, of a harpsichord.'[9]

8

Cage already knew such experimentation with the sound of the piano from his teacher Henry Cowell. In Cowells work Aolian Harp for example the player has to play on the piano strings. The prepared piano also has a tradition in the American inventiveness, which I mentioned at the beginning. As Cage said, American Bach societies, which couldnt obtain 18th Century harpsichords, employed thumb tacks on the piano hammers. Or he mentioned jazz pianists, who put newspapers on the strings.[10]

SEITE: 55

9

John Cage composed about 35 pieces for prepared piano between 1940 and 1954. Again these are mainly works, which were written for dance. In the first pieces the preparation is not very extensive, and it is also notated not very precisely. But I also have to say that we may not forget of course that Cage did not publish his first pieces. So we cannot be sure whether Cages intentions really have been so free, or if they only seem so because he did not write down the specifications exactly.

10

Another example is In the Name of the Holocaust, written in 1942. Here it must be mentioned that Cage demands special playing techniques besides the preparation itself, plucking the strings, playing clusters with the arm or the flat hand.

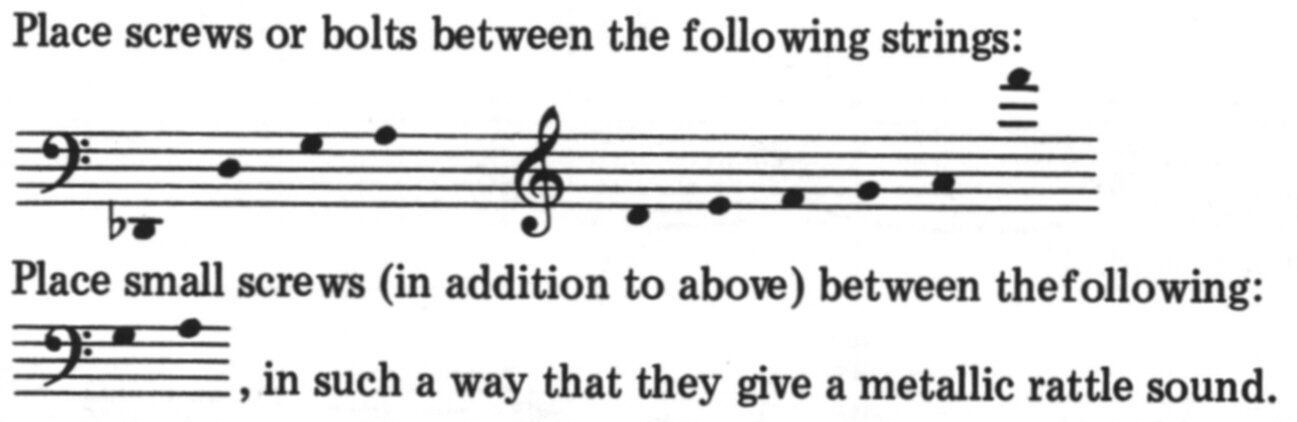

Fig. 1:

In the Name of the Holocaust (1942)[11]

The two pieces for two prepared pianos, A Book Of Music (1944) and the Three Dances (1945), can be indicated as a decisive event for Cage's composing. Both works are dedicated to professional pianists, Robert Fizdale and Arthur Gold. So far, usually Cage himself had played his piano works; of course he could play piano quite well, but it really cannot be said that he was a virtuoso. Therefore his early works are not very difficult to play.

12

Gradually Cage becomes established as a composer, and so his works now become performed more often by professional musicians. His compositions become more complex and more extensive. The largest and also most important work for prepared piano, Cage writes in the years 1946 to 1948: the Sonatas & Interludes. In this work his occupation with Indian culture finds its musical expression. In the year 1945 Cage did

SEITE: 56

meet the Indian singer and tabla player Gita Sarabhai. She introduced him to the Indian world of thoughts.

'After reading the work of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, I decided to attempt the expression in music of the "permanent emotions" of Indian traditions: the heroic, the erotic, the wondrous, the mirthful, sorrow, fear, anger, the odious and their common tendency toward tranquility.'[12]

Cage also got to know the Indian world of sounds, which mirrors these Indian emotions, the so-called Rasas. It is the ever-floating character of Indian music, its resting in itself, which we can find also in the Sonatas & Interludes. So with Indian music Cage widens the horizon of his musical cosmos. But Cage did not only pick up Indian sounds for his sound collection. Still more obvious is the tonal relationship with Javanese gamelan music. Cage became acquainted with gamelan music through the lectures of Henry Cowell, lectures on eastern music and folk music of various countries.

13

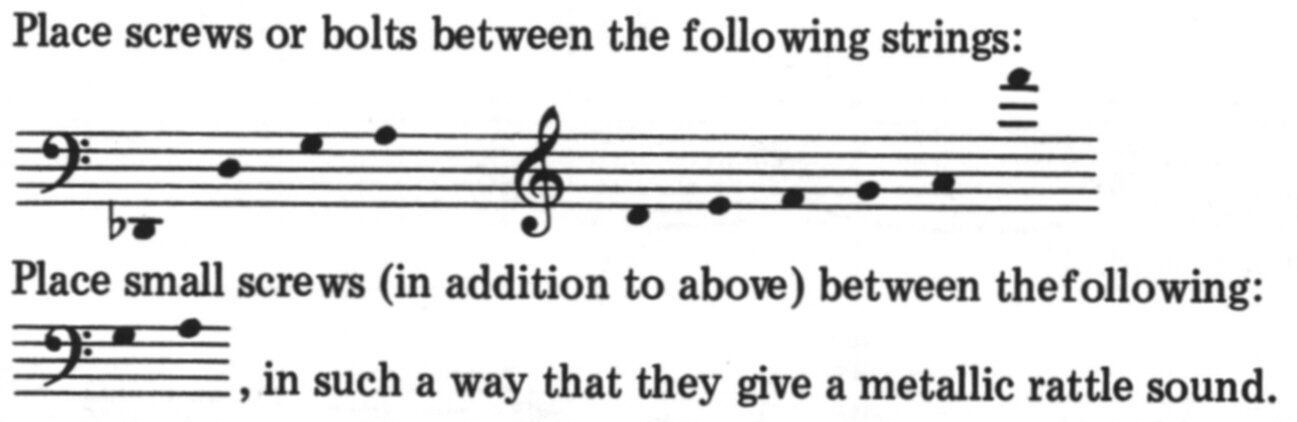

The preparation list of the Sonatas & Interludes is extremely detailed:

Fig. 2:

Preparation list of Sonatas & Interludes (1946-48)

The position of the materials is prescribed exactly at a sixteenth of an inch. And, for example, Cage requires not less than five different kinds of bolts. Cage explained in which way he determined the position of the materials:

SEITE: 57

'I placed objects on the strings, deciding their position according to the sounds that resulted. Having those preparations of the piano and playing with them on the keyboard in an improvisatory way, I found melodies and combinations of sounds that worked with the given structure. Just as you go along the beach and pick up pretty shells that please you, I go into the piano and find sounds I like.'[13]

So Cage here describes himself as a collector of sounds.

14

The apparent accuracy of the preparation is deceiving; Cage ignores that the strings of different grand pianos have different dimensions. And what is the difference for example between an ordinary bolt and a medium bolt? So besides all the accuracy, it is above all the feeling for the sound which finally has to decide about the kind and position of the materials.

'There are not only differences in screws or bolts but also in pianos (of the same make and size). I would say then that using my table as a set of suggestions, chose [sic] objects that do not become dislodged or in other ways stand out of the music. You will often be able to tell whether your preparation is good or not if the cadences "work".'[14]

The materials Cage uses are: wood, screws, bolts, nuts, plastic, rubber, coins, weather stripping, bamboo or cloth.

15

In the year 1950 John Cage composes the Concerto for Prepared piano. This is the first time he works with chance operations. At the same time the period of the prepared piano comes to its end. Composing with chance and indeterminacy becomes the focus of attention. This also characterises his last two works for prepared piano. In 3157.9864 for a Pianist and 3446.776 for a Pianist (both 1954) the materials are determined only very vaguely.

SEITE: 58

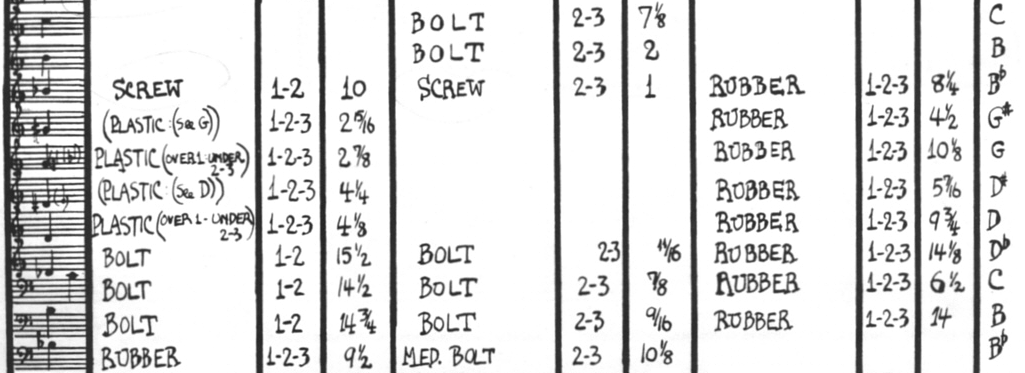

Fig. 3:

3446.776 for a Pianist (1954)

16

For example, the "P" stands for plastic, but one can use glass or bone as well. The "x" means that one can use any object. Also the position is not determined any longer. And, in the course of the playing one has to change the position of the materials, to remove or to add materials. So the sound result depends also on chance now.

17

Let us look back: In his first works for prepared piano Cage did need only few materials, and the specifications about the position have been rather vague. The selection of the materials became ever more complex up to the Sonatas & Interludes, the specifications ever more exactly. In 3157.9864 for a Pianist and 3446.776 for a Pianist the piano may become prepared finally with all imaginable materials. And as I said, the position of the materials is changed in the course of the playing, materials are added or removed. So the preparation becomes ever more extended in the course of the years. And beyond it, Cage now also requires noises, produced by other freely chosen means. This can be a whistle, but the shaking of a matchbox as well. As an example we can take a look at the instrumentation of Water Walk: 'Employed here are roses in a vase, a stove and a rubber fish, a quail call; [...] a goose whistle, a bath tub, an exploding paper container, and a bottle of Campari.'[15]

SEITE: 59

18

Thus Cage extended his sound collection beginning in the first years with the pure, unprepared instrument; then going on to the preparation with determined materials, later then using undetermined materials. The next step is to use all imaginable objects which can produce sounds. The last consequence of this sound extension is to integrate the entire sound range of the environment into art. As Cage at the beginning of the thirties already was fascinated by the sounds surrounding him on the road, he is ever more fascinated by the coincidence of different sounds. For him, being surrounded by sounds seems to have been an everlasting event if we can trust his words:

'I love living on Sixth Avenue. [...] It has more sounds, and totally unpredictable sounds, than any place Ive ever lived. The traffic never stops, night and day. Every now and then a horn, siren, screeching brakes - extremely interesting and always unpredictable.' (1978)[16]

19

Cage already experienced this way to perceive the environment when he met the painter Mark Tobey in the Thirties.

'He would continually stop to notice something surprising everywhere - on the side of a shack or in a space ... which we normally didnt notice when we were walking, and his gaze would immediately turn them into a work of art.'[17]

Consequently John Cage, the sound collector, pushed the borders of the musical horizon ever more in the course of his life. And just the same he pushed the borders of the idea of music as far as possible.

SEITE: 60

Works for prepared piano

Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939)

Percussion, muted piano, 2 record player (four performer)

Order number: 6716

Bacchanale (1940)

Order number: 6784, 67886a

Imaginary Landscape No. 2 (1940)

Percussion, records of various frequencies, prepared piano

Second Construction (1940)

Percussion quartet including prepared piano

Order number: 6791

Totem Ancestor (1942)

Order number: 6762

And The Earth Shall Bear Again (1942)

Order number: 6811, 67886a

Primitive (1942)

Order number: 66756, 67886a

In the Name of the Holocaust (1942)

Order number: 66755, 67886a

Shimmera (1942)

Four Dances (1942-43)

Prepared piano, percussion, voice

Order number: 67450

What We've So Proudly Hailed (1942-43)

Prepared piano, percussion, voice

Later published as: Four Dances

SEITE: 61

Lidice (1943)

Amores (1943)

Percussion (trios) and prepared piano

Order number: 6264

Our Spring Will Come (1943)

Order number: 66763, 67886a

She Is Asleep (1943)

Percussion, voice, piano or prepared piano

Order number: 6746, 6747

A Room (1943)

Piano or prepared piano

Order number: 6970, 67830

Meditation (1943)

First part identical to "Tossed As It Is Untroubled" (1943).

Tossed As It Is Untroubled (Meditation) (1943)

Order number: 6722, 67886a

Triple-Paced (1943)

Piano (1944 version for prepared piano)

The Perilous Night (1943-44)

Order number: 6741, 67886a

Prelude for Meditation (1944)

Order number: 6742, 67886b

Root of an Unfocus (1944)

Order number: 6743, 67886b

Spontaneous Earth (1944)

Order number: 66753, 67886b

The Unavailable Memory of (1944)

Order number: 66764, 67886b

A Valentine Out of Season (1944)

Order number: 6766, 67886b

A Book of Music (1944)

Two prepared pianos

Order number: 6702

Mysterious Adventure (1944-45)

Order number: 6787, 67886b

Three Dances (1944-45)

2 prepared pianos

Order number: 6760

Daughters of the Lonesome Isle (1945)

Order number: 6785, 67886b

Music for Marcel Duchamp (1947)

Order number: 6728, 67886b

Sonatas and Interludes (1946-48)

Order number: 6755

Music for "Works of Calder" (1949-50)

Prepared piano and recorded sounds

Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra (1950-51)

Prepared piano and chamber orchestra

Order number: 6706

Two Pastorales (1951-52)

Prepared piano and two whistles

Order number: 6765

34'46.776" for a Pianist (1954)

Piano (with changing preparations)

Order number: 6781

31'57.9864" for a Pianist (1954)

Piano (with changing preparations)

Order number: 6780

SEITE: 62

Notes

1 This is a revised version of an article published in: Peter Rautmann and Nicolas Schalz (eds.), Anarchische Harmonie - John Cage und die Zukunft der Künste, Bremen 2002, p. 141-149.

2 David Revill, The Roaring Silence: John Cage, London 1992, p.14.

3 John Cage, An Autobiographical Statement (1989), from http://newalbion.com/artists/cagej/autobiog.html.

10 John Cage, text published in CD-booklet "Sonatas & Interludes" played by Maro Ajemian, New York 1995 Composers Recordings Inc., CD 700.

11 All musical examples © by Henmar Press, New York. Published with permission from C. F. Peters, Musikverlag, Frankfurt/M.

12 John Cage, text published in CD-booklet "Sonatas & Interludes" played by Maro Ajemian, New York 1995 Composers Recordings Inc., CD 700.

15 David Revill, The Roaring Silence, p. 194.

Dokument erstellt am 2. Februar 2003